The collapse of the FDA

FDA's power comes from its reputation. What happens when that reputation is gone?

Earlier this week, the New York Times published an article by Jeneen Interlandi, “Inside the Collapse of the F.D.A.”, that has been making waves in my circle of former and current FDA employees. It’s a fascinating and well-researched article, and I hope everyone who follows the issues discussed in this blog takes the time to read it.

Reading the article, I found myself nodding my head a lot; much of it rang true to me. First and foremost, I hope the article showed how remarkable the FDA has been as an institution. Its staff are genuinely dedicated to making the right decision, driven by science, and independent from industry influence. The article cites Peter Lurie, a former deputy commissioner at FDA, saying that most FDA meetings “involved smart people trying to achieve shared objectives. Political ideologies or feelings about industry never came up at all and would not have mattered if they did.” Given the power FDA wields, and the opportunities that power presents for corruption, the FDA’s level of integrity and independence is a small miracle.

I was particularly touched by the article’s depiction of FDA staff’s efforts to preserve the agency’s unique knowledge and culture. Many former FDA employees I have met have expressed a similar desire – I’ve heard it shared by other former federal employees as well. In fact, it is one of the reasons I started this blog in the first place; I wanted to share the story of how FDA and the institutions that surround it came to exist, in part to ensure they can be preserved and, if necessary, rebuilt. I am sure I will spend lots of time criticizing the agency in this blog, but I want to also convey what an impressive achievement its existence is. As I noted in my very first blog post, much of our modern, rigorous research system – and the health benefits it has produced – exist in large part because of the FDA.

With all of that said, I want to challenge the framing of the article a bit. As the author notes, FDA is under unprecedented pressure. Agency morale is “tanking” and its capacity to do its work is greatly diminished. Yet I suspect (and hope) it’s too soon to say that the agency has “collapsed” – at least from a functional standpoint. I do think collapse is a real risk, and we should be thinking carefully about what exactly an FDA collapse would look like so that we can respond to it appropriately. Some signs of collapse would be obvious: more missed review deadlines, more stories leaking about political interference in agency decision-making, and more public health crises. But so much of the agency’s work is not immediately visible, including its efforts to inspect facilities, promote food and drug safety, lower drug costs, improve drug quality, and advance drug research. Far too often, the invisible stuff is targeted for cuts first. I hope industry, the public, and journalists take extra steps to track how well FDA is doing at these less-visible tasks, and how we can restore capabilities that are being diminished or lost.

FDA is a victim of a society-wide collapse in trust

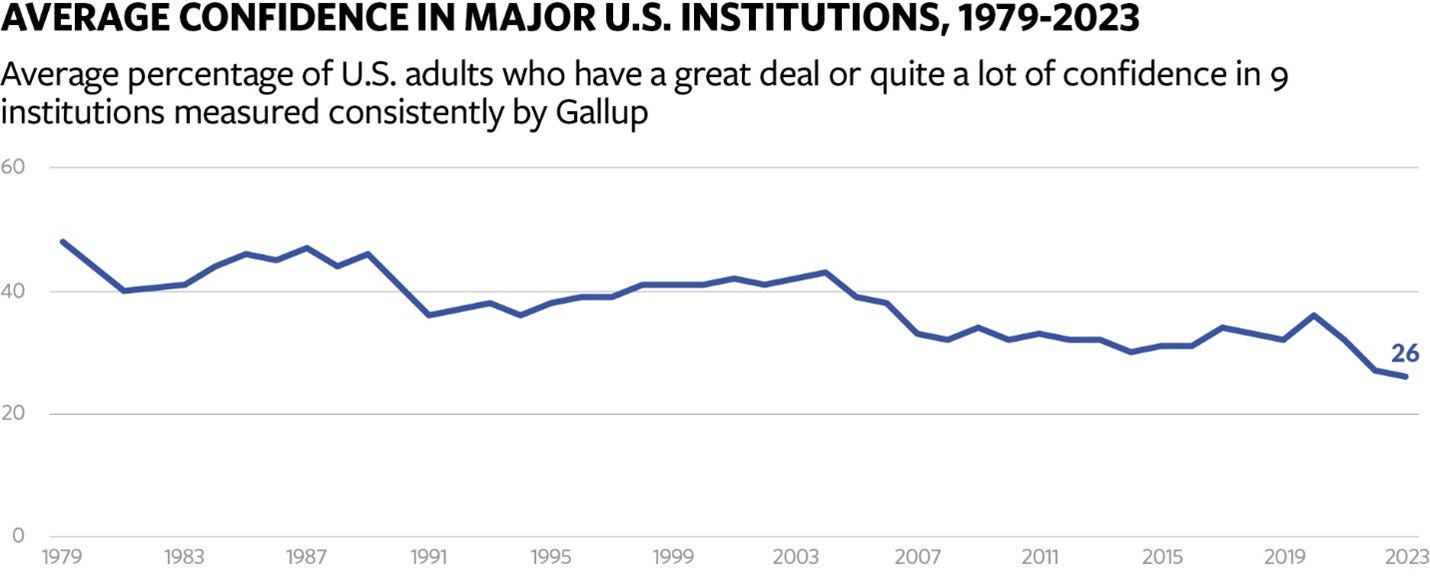

While I’m not certain the FDA has collapsed, I do believe the agency is in grave danger, driven largely by a loss in its reputation. In her New York Times article, Interlandi cites a 2010 history of FDA written by Daniel Carpenter, “Reputation and Power”. Carpenter’s thesis was that FDA had successfully established itself as an independent center of power in the government by establishing a strong reputation for scientific rigor, and that much of its behavior could be explained by its desire to maintain that reputation. That reputation, in turn, is what has allowed FDA to be a powerful and influential regulator. Regardless of how you feel about the FDA, it does appear as though the era described by that book is coming to an end. The New York Times article describes, in detail, how the trust and reputation that girded FDA has eroded over time, and made the agency more vulnerable, leading to the takeover by RFK Jr. The statistics bear this out, showing that trust in FDA is very low nowadays.

I don’t think this decline in trust will be easily reversed. Carpenter’s book was published while powerful forces were changing the nature of how trust and reputation were earned and maintained. Beyond the specific missteps and oversights the agency made, I see these more fundamental forces as the key driver of FDA’s decline and its current predicament. As the author Martin Gurri describes, while governments and elites once held a monopoly over information, that is no longer the case. Instead, the public must contend with a “tsunami” of information driven by modern media and the internet. Some of that information is inaccurate: falsehoods, conspiracy theories, misinformation, and the like. Some of it is accurate but unflattering; the failures of elite institutions like FDA are simply far more visible to the public than they once were. This tsunami has brought down trust in institutions across society, and this collapse in trust goes much further than just the FDA.

In explaining the decline in trust in FDA, the New York Times article does not spend much time on these broader forces. Instead, it cites a series of crises and missteps: the slow approval of HIV drugs, the Agency’s mishandling of opioids, the Vioxx scandal, and the approval of Aduhelm. While each of these crises accelerated the decline in FDA’s reputation, the reality is that FDA’s reputation would never have survived intact in this new environment.

In truth, the trust the public placed in FDA was based on a flawed premise. For decades, FDA approval was considered an unimpeachable “gold standard” and FDA’s statements held enormous weight in both the medical establishment and the public consciousness. I believe we were better off in that world. By and large, FDA got important decisions right - or at least, more right than almost any realistic alternative institution would have. The FDA also learned and improved over time, speeding up reviews, providing more regulatory flexibility, and improving oversight of approved drugs. Yet the agency was not infallible. It was, at times, excessively risk-averse in approving products. It also faced genuine constraints in wielding its power effectively, particularly when it came to oversight of drugs that were already approved like opioids. And even where it was able to exercise its authority, the agency had an inherently difficult job to do and could not possibly please everybody.

FDA is an admirable agency, but it is led by flawed human beings. That means it will make errors in judgment and face normal political constraints. There are always stakeholders to be appeased and competing interests to be weighed. There is no way to please everyone. And each time someone is displeased, they will share their views online and find a receptive audience willing to amplify and even distort those views. No amount of public rectitude or disinformation management on FDA’s part is going to prevent that from happening.

After the trust is gone, what comes next?

It is because of these forces that I am skeptical that FDA can restore the trust the public once held in it. The forces that have eroded that trust are powerful and largely beyond the agency’s control. But that doesn’t mean the agency shouldn’t try its best. The agency still has reputational capital left and should do what it can to preserve it for as long as possible.

Preserving what trust is left will take a delicate balance. During Rob Califf’s most recent term as FDA commissioner, he launched a campaign against “misinformation and disinformation”: dangerous falsehoods that spread online that undermined FDA’s public health messages and endangered the public. I empathized with what Califf was trying to do - the campaign was rooted in genuine concerns that false health beliefs could undermine public health and ought to be corrected, and an understanding that technology had fundamentally changed how misinformation spread. Despite that, I fear that Califf’s public campaign might have alienated the very audience he was trying to reach; a suspicious public may not want to hear that they’re the target of a government-run “anti-disinformation” campaign. Likewise, the article discusses the pros and cons of greater transparency on FDA’s part in its decision-making. As much as I value transparency for its own sake, I do agree that it can be used against the agency; the more nuanced truth behind FDA’s actions may benefit the savvy readers of this blog but may be distorted as it reaches the general public.

There is also a question of what those of us outside the agency should be doing. That brings me to one of the most interesting questions raised by the New York Times article: in an era when so many vital institutions like FDA are threatened, what is the role of the “loyal critic” who both values the institution but also wants to see it improved? The article cites so-called F.D.A. watchdogs who may have, through their criticisms, cultivated the environment of mistrust that led to FDA’s current predicament. I would advise these critics to recalibrate their messages.1 People who believe that we can demand more from institutions like FDA also need to praise those institutions when they do their jobs well and make it clear how much we have to lose when those institutions are threatened.

Finally, we should start to look at what the FDA of the future might look like when much of the agency’s reputation and expertise has been depleted. I hope efforts like this blog are part of the answer. We need experts to write down and share what we have learned from our experiences at the agency. But we also need to be creative and envision how we might approach public health and regulation differently in a new, low-trust world. In some cases, that might even mean stakeholders look beyond the agency to find ways to ensure that FDA’s mission endures and succeeds2.

I also hope these critics recalibrate their policy priorities. Many were both naïve about how politics works, and excessively cynical about the FDA itself, which led to errors in judgment. For example, calling for an end to user fees was always more likely to lead to the agency being defunded than to useful reform.

For example, in my AI post, I noted that we might benefit from public-private collaboration on AI models that support regulatory science. I’ll be sharing more ideas along those lines in future posts.